Beginning in 1890, Canada's

Remembrance Day was called "Decoration Day" - and was commemorated in May

similar to the the USA's Memorial Day, until 1931 it was moved to November 11

by an act of parliament and renamed "Remembrance Day."

Canada's military memorial day was first observed in May 1890, long before the South African War and the

First World War.

The first commemoration was first held on the grounds of University of Toronto

across the street from Queens Park, partly in protest by

Canadian Militia veterans who had fought at the Battle of Ridgeway on June 2,

1866 defending Canada from a force of Irish-American Fenian insurgents invading from the USA

across the Niagara River at Fort Erie, and partly to remember the nine militia

soldiers from Toronto's Queen's Own Rifles Regiment who were killed in action at

Ridgeway, arguably the first Canadian casualties from the modern Canadian Armed

Forces.

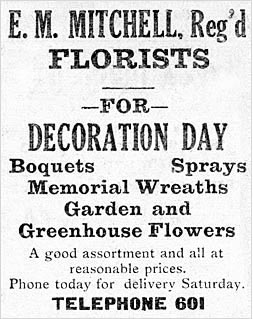

It was called "Decoration Day" because fallen soldier's graves were "decorated"

with flowers.

The veterans and public had gathered at the 'Volunteers Monument' in Toronto to protest the Canadian government's lack of recognition of the veterans and remember those killed in action at Ridgeway, Canada's first "modern battle", one first fought in the age of the telegraph, steam power, rifled barrels, a free press and parliamentary democracy in Canada ("Responsible Government.)

On June 1,

1866, after nearly fifty years of peace since the War of 1812, Canada was

invaded from the United States by an insurgent army of Irish-American Fenians

determined to expel British rule from Ireland by taking Canada hostage.

A 1,000 man heavily armed vanguard of battle

hardened Civil War veterans from the US and former Confederate army seized the town of

Fort Erie and began moving towards the Welland Canal next, threatening to

destroy it.

On the morning of June 2, near the village of Ridgeway west of Fort Erie, they were

intercepted by a brigade of Canadian militia from the Queen’s Own Rifles (QOR)

of Toronto and 13th Battalion of Hamilton (today the Royal Hamilton

Light Infantry (RHLI) in what became Canada’s first modern battle to be fought

exclusively by Canadian troops and led entirely by Canadian officers:

the Battle of Ridgeway.

On June 1,

1866, after nearly fifty years of peace since the War of 1812, Canada was

invaded from the United States by an insurgent army of Irish-American Fenians

determined to expel British rule from Ireland by taking Canada hostage.

A 1,000 man heavily armed vanguard of battle

hardened Civil War veterans from the US and former Confederate army seized the town of

Fort Erie and began moving towards the Welland Canal next, threatening to

destroy it.

On the morning of June 2, near the village of Ridgeway west of Fort Erie, they were

intercepted by a brigade of Canadian militia from the Queen’s Own Rifles (QOR)

of Toronto and 13th Battalion of Hamilton (today the Royal Hamilton

Light Infantry (RHLI) in what became Canada’s first modern battle to be fought

exclusively by Canadian troops and led entirely by Canadian officers:

the Battle of Ridgeway.

Nine riflemen from the Queen's Own Rifles, three of them University of Toronto

student volunteers hastily called out

from their final exams on the day before, were killed in the battle before the

Canadian forces were forced to fall back by the more experienced and better

armed Fenian insurgents. Twenty-two more

Canadians would die of either wounds or disease sustained during the fighting or

on frontier duty during the Fenian Raids that would also extend into Quebec in

the following week.

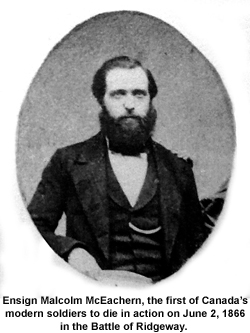

Beginning with the first casualty, Ensign Malcolm McEachern killed in the

early minutes of the battle on June 2, these thirty-one casualties were the

first 31 of nearly 120,000 Canadian servicemen to fall in military service from the South

African War to Afghanistan.

Except for

miniscule payments to those severely wounded in the battle, or to the widows and

orphans of those killed, the veterans

received from the government no acknowledgement, no honours, decorations, pensions or awards for their

service in the defence of Canada during the Fenian Raids.

The

Canadian Volunteers Monument,

raised in 1870 near Queens Park (Toronto's currently oldest standing public monument)

was paid for entirely by private donations. As Canadian-American relations

warmed towards the mutual "undefended border" further public discourse or

commemoration of

a battle defending against an invasion from across the U.S. border became

unpolitic, inconvenient and impolite.

The more than eight hundred veterans who fought at Ridgeway were forgotten and

ignored for twenty-five years following the battle.

Except for

miniscule payments to those severely wounded in the battle, or to the widows and

orphans of those killed, the veterans

received from the government no acknowledgement, no honours, decorations, pensions or awards for their

service in the defence of Canada during the Fenian Raids.

The

Canadian Volunteers Monument,

raised in 1870 near Queens Park (Toronto's currently oldest standing public monument)

was paid for entirely by private donations. As Canadian-American relations

warmed towards the mutual "undefended border" further public discourse or

commemoration of

a battle defending against an invasion from across the U.S. border became

unpolitic, inconvenient and impolite.

The more than eight hundred veterans who fought at Ridgeway were forgotten and

ignored for twenty-five years following the battle.

In May 1890 after nearly

two and a half decades of silence, a short paragraph in the

Globe, “Ridgeway Remembered,” reported that the

Veterans of ’66 Association had “taken the

matter in hand” and would meet

in protest

on the

twenty-fourth anniversary of the battle to lay flowers

and wreaths

at the

Canadian Volunteers Monument

near Queen’s Park.[1]

The

Globe described the

occasion

under the headline “Our Decoration Day” and

promised that from now on the day

would be commemorated annually in the same

way that Americans memorialize their war dead.[2]

The next year in

Hamilton, it was reported that the Ridgeway veterans of the Thirteenth Battalion

had come together for a reunion for the first time in twenty-five years.[3]

The national memorialization of Ridgeway had begun and would now unfold from

about 1890 to1925, resulting in a thirty-five year renaissance of

acknowledgments, awards, speeches, ceremonies, reminiscences, and published

accounts, some sponsored by regional historical societies.

On June 2, 1891 in Toronto, the twenty-fifth

anniversary of the battle, thirty thousand people gathered at the

Volunteers Monument. Spectators

climbed up on the scaffolding of the newly constructed Parliament Buildings onto

lumber piled up at the site and into the trees of the park. Schoolchildren covered the monument in

wreaths and leafy plants,

some bearing the names of those killed at Ridgeway.

Not a practice followed in Britain at the time, this was a

gesture adopted from the United States where, after the Civil War, flowers were

laid on military graves in May on national Memorial Day, or Decoration Day, as

it was also known.

Toronto’s militia

regiments, along with 450 boys from the public school drill corps carrying

muskets and accompanied by 30 Toronto Police constables, escorted several

hundred Veterans of ’66 from the drill shed at Simcoe Street along a route

packed with fifty thousand spectators.[4]

The

“decoration” of the monument by Toronto’s schoolchildren became an annual

ritual. It was the beginning of

Canada’s

first remembrance day.[5]

Decoration

Day would eventually encompass the remembrance of those who died in the

1885

Northwest Rebellion[6] and later

the

South African War

1899-1903,

with the first joint remembrance ceremony being held in

June 1903.[7]

Throughout the Great War (First World War) the mounting casualties were mourned

on Decoration Day in June long before there came to be a November 11 armistice

in 1918.

Decoration

Day would eventually encompass the remembrance of those who died in the

1885

Northwest Rebellion[6] and later

the

South African War

1899-1903,

with the first joint remembrance ceremony being held in

June 1903.[7]

Throughout the Great War (First World War) the mounting casualties were mourned

on Decoration Day in June long before there came to be a November 11 armistice

in 1918.

Until 1931, Decoration Day

was Canada’s

popular national

memorial day, held in late May or early June and in some places as late

as August.[8]

It is still commemorated today in some of the Ontario rural communities that

witnessed the Fenian Raids or saw their sons die or be broken in them. In 2010

the town of Dunnville held its 113th annual Decoration Day on June 6,[9]

while Caledonia held its own on May 30.[10]

By 1895 the Veterans of ’66 Association had organized a national petition for the recognition of all the volunteers who served during the Fenian Raids.[11] In January 1899, in response to the petition, Britain authorized a Canadian General Service Medal for veterans of the 1866 and 1870 Fenian Raids and the 1870 Red River Rebellion. Anybody who was on active service in the field, had served as a guard at any point when an attack from the enemy was expected, or had been detailed for some specific service or duty was eligible for the medal upon applying for it—it was not issued automatically. There were 15,300 of these medals issued to Canadians with their individual names and units engraved on the rim. (Another 1,368 were claimed by British veterans.)[12] The medal was issued by Britain just in time for the call on Canada to help in the upcoming South African War. The Canadian federal government acquiesced to the British medal but added nothing of its own for the veterans of Ridgeway as it did in the case of the Red River Expedition and Northwest Rebellion, whose veterans were granted 160 acres of Crown land, whereas those who fought in South Africa would get 320 acres.[13] In the end, in 1901 the province of Ontario undertook to grant its Fenian Raid veterans 160 acres of provincial land if they applied for it.[14]

While

the medals and recognition might have healed some hurt pride, the process of

historical restoration was incomplete. The public events were accompanied by

newspaper articles on the histories of the battle and on the units who fought in

it. Over the next two decades, witnesses and veterans of the battle began

publishing their recollections in popular magazines and historical journals and

in papers presented at historical society talks.[15]

But these fragmentary sources were never assembled or collated in any new

comprehensive history of the battle other than the one authored by Captain John

A. Macdonald in 1910. His book, Troublous

Times in Canada: The History of the Fenian Raids of 1866 and 1870, would be

the last on the battle for more than a century to follow. It added nothing new

but lamented how, “It is a strange fact that Canadian authors and historians do

not seem to have fully realized the gravity of the situation that then existed,

as the event has been passed over by them with the barest possible mention. Thus

the people of the present generation know very little of the Fenian troubles of

1866 and 1870, and the great mass of the young Canadian boys and girls who are

being educated in our Public Schools and Colleges are in total ignorance of the

grave danger which cast dark shadows over this fair and prosperous Dominion in

those stormy days.”[16]

Nothing had

changed in the hundred years

since those

words had been written which is why the author of this article researched and

wrote Ridgeway in 2011.

While

the medals and recognition might have healed some hurt pride, the process of

historical restoration was incomplete. The public events were accompanied by

newspaper articles on the histories of the battle and on the units who fought in

it. Over the next two decades, witnesses and veterans of the battle began

publishing their recollections in popular magazines and historical journals and

in papers presented at historical society talks.[15]

But these fragmentary sources were never assembled or collated in any new

comprehensive history of the battle other than the one authored by Captain John

A. Macdonald in 1910. His book, Troublous

Times in Canada: The History of the Fenian Raids of 1866 and 1870, would be

the last on the battle for more than a century to follow. It added nothing new

but lamented how, “It is a strange fact that Canadian authors and historians do

not seem to have fully realized the gravity of the situation that then existed,

as the event has been passed over by them with the barest possible mention. Thus

the people of the present generation know very little of the Fenian troubles of

1866 and 1870, and the great mass of the young Canadian boys and girls who are

being educated in our Public Schools and Colleges are in total ignorance of the

grave danger which cast dark shadows over this fair and prosperous Dominion in

those stormy days.”[16]

Nothing had

changed in the hundred years

since those

words had been written which is why the author of this article researched and

wrote Ridgeway in 2011.

In the early 1900s, mention of “Decoration Day” began to fade from the

newspapers.

By 1903 the commemoration coverage in the

Globe was reduced once again to a

small paragraph, and by 1907 the event had been moved to the privacy of the

cemeteries where the fallen were buried. It was no longer the public event it

had been in the 1890s and gradually became disconnected from June 2 and moved

closer to Victoria Day in May. After years of peace following the South African

War, the Great War of 1914 to 1918 sadly revived Decoration Day as Canada’s

national memorial day.

In the early 1900s, mention of “Decoration Day” began to fade from the

newspapers.

By 1903 the commemoration coverage in the

Globe was reduced once again to a

small paragraph, and by 1907 the event had been moved to the privacy of the

cemeteries where the fallen were buried. It was no longer the public event it

had been in the 1890s and gradually became disconnected from June 2 and moved

closer to Victoria Day in May. After years of peace following the South African

War, the Great War of 1914 to 1918 sadly revived Decoration Day as Canada’s

national memorial day.

In

1916, on the fiftieth anniversary of Ridgeway the cornerstone for a monument was

laid at a five-acre site on the Garrison Road end of the battlefield,

approximately where the schoolhouse stood and where the ridge began its rise

toward the north. In 1921 the site was made a National Historic Battlefield to

be administrated by Parks Canada with a cairn to mark the spot. One of the

surviving cabins that was used during the battle as a field hospital and in

which Canada’s

first military casualties were treated, was relocated to the site. Farther down the road

in the town of Ridgeway are a battlefield museum and Fort Erie’s historical

archives. The battlefield itself, east of Ridge Road between Garrison and Bertie

roads, until very recently had remained untouched, although the orchards had

long disappeared, but it is now facing extinction under creeping housing

developments.

In

1916, on the fiftieth anniversary of Ridgeway the cornerstone for a monument was

laid at a five-acre site on the Garrison Road end of the battlefield,

approximately where the schoolhouse stood and where the ridge began its rise

toward the north. In 1921 the site was made a National Historic Battlefield to

be administrated by Parks Canada with a cairn to mark the spot. One of the

surviving cabins that was used during the battle as a field hospital and in

which Canada’s

first military casualties were treated, was relocated to the site. Farther down the road

in the town of Ridgeway are a battlefield museum and Fort Erie’s historical

archives. The battlefield itself, east of Ridge Road between Garrison and Bertie

roads, until very recently had remained untouched, although the orchards had

long disappeared, but it is now facing extinction under creeping housing

developments.

On June 1, 1930, eight surviving Ridgeway veterans in their eighties marched in St. Catharines in the last Decoration Day parade to be held there.[17] After that they came no more. On November 9, 1936, the Hamilton Spectator noted that “the last but one” of the remaining Fenian Raid veterans from the Thirteenth Battalion, Thomas Kilvington, had died. Allan Land, ninety-two years old, was the only one left standing of the “boys” from Hamilton.[18]

Following the First World

War, Decoration Day in late May or early June (and even as late as August in

some communities) had continued to be Canada’s

national memorial day for all veterans until an Act of Parliament in 1931, in

order to "harmonize it with Commonwealth practice"

transformed November 11 "Armistice Day" into "Remembrance Day" while

Thanksgiving Day was moved back a month to October.[19] The

Ridgeway veterans, of whom those still living were aged men, were forgotten and excluded from the new Remembrance Day, the

honour extended by Veterans Affairs Canada only as far back as 1899, to those who

fought in the South African War.[20]

At this writing, the fallen of Ridgeway are not listed in Canada’s National

Books of Remembrance and their graves scattered across Ontario, the land they

defended with their lives, remain

forgotten and uncared for by the government, abandoned without national historic

monument status or as Canadian war graves.[21]

Following the First World

War, Decoration Day in late May or early June (and even as late as August in

some communities) had continued to be Canada’s

national memorial day for all veterans until an Act of Parliament in 1931, in

order to "harmonize it with Commonwealth practice"

transformed November 11 "Armistice Day" into "Remembrance Day" while

Thanksgiving Day was moved back a month to October.[19] The

Ridgeway veterans, of whom those still living were aged men, were forgotten and excluded from the new Remembrance Day, the

honour extended by Veterans Affairs Canada only as far back as 1899, to those who

fought in the South African War.[20]

At this writing, the fallen of Ridgeway are not listed in Canada’s National

Books of Remembrance and their graves scattered across Ontario, the land they

defended with their lives, remain

forgotten and uncared for by the government, abandoned without national historic

monument status or as Canadian war graves.[21]

ENDNOTES

[1]

Globe, May 31, 1890.

[2]

Globe, June 3, 1890.

[3]

Hamilton Spectator, June 3, 1891.

[4]

Globe, June 3, 1891.

[5]

Paul Maroney, “‘Lest We Forget’: War and Meaning in English Canada,

1885–1914,” Journal of Canadian Studies, Vol. 32, No. 4 (Winter 1997/1998);

Globe, May 30, 1896.

[6]

Globe, May 30, 1896.

[7]

Maroney, “‘Lest We Forget.’”

[8]

http://www.vac-acc.gc.ca/remembers/sub.cfm?source=teach_resources/remdayfact

[retrieved January 2, 2010].

[9]

Cathy Pelletier, “Decoration Day in Dunnville,”

The Chronicle, June 8, 2010,

http://www.dunnvillechronicle.com/ArticleDisplay.aspx?e=2614364

[accessed July 6, 2010].

[10]

Katie Dawson, “Honouring Veterans During Decoration Day Ceremony,”

Cambridge Reporter, May 19,

2010, http://www.cambridgereporter.com/news/article/210556 [accessed

July 6, 2010].

[11]

Globe, March 11, 1896; April 12, 1897; May 24, 1897; Captain

Macdonald, p. 185; Committee of Citizens Chosen to Represent the City of

Toronto, “To The Queen’s Most Excellent Majesty,” circa 1897 [CIHM NNo.

46333].

[12]

http://www.vac-acc.gc.ca/remembers/sub.cfm?source=collections/cmdp/mainmenu/group03/cgsm

[retrieved Oct. 10, 2009].

[13]

Captain Macdonald, pp. 186–188.

[14]

RG 1-99 Fenian land grant records, Archives of Ontario

[15]

Globe, July 4, 1896, and January 7, 1899;

Canadian Magazine, November, December 1897, January 1898, July 1899.

[16]

Captain Macdonald, p. 5.

[17]

Globe, June 2, 1930.

[18]

Hamilton Spectator, November 9, 1936.

[19]

http://www.vac-acc.gc.ca/general/sub.cfm?source=teach_resources/remdayfact

and

www.calendar-updates.com/info/holidays/canada/remembrance.aspx

[retrieved October 10, 1866]. James Wood argues that the militia lobbied in

the 1890s to move Thanksgiving Day to October for the Canadian holiday

in the hopes of enjoying better weather and larger audiences for its

church parade. See James Wood, Militia Myths: Ideas of the Canadian

Citizen Soldier 1896–1921, Vancouver-Toronto: University of British

Columbia Press, 2010. p. 30.

[20]

http://www.vac-acc.gc.ca/remembers/sub.cfm?source=teach_resources/remdayfact

[retrieved January 7, 2010].